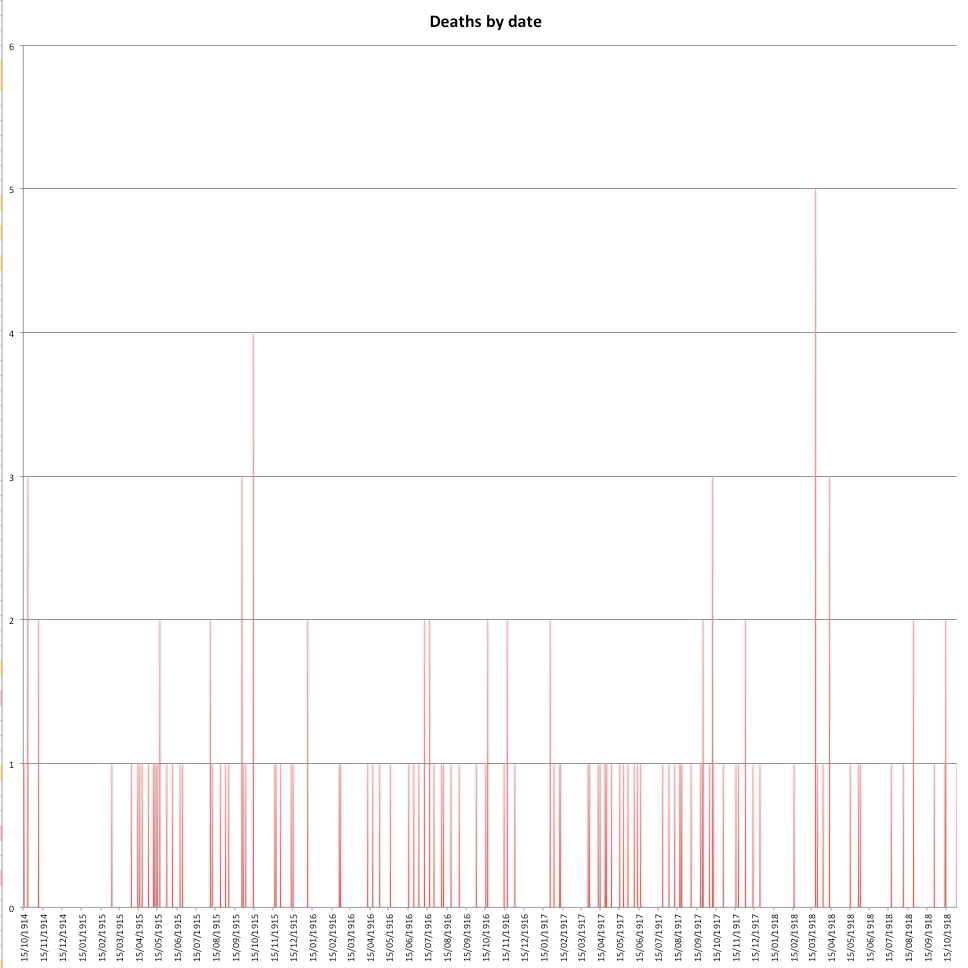

Mapping the numbers of deaths against dates produces a graph which reminded me of a seismograph: highlighting some of the most awful days and an awful awful war.

Clusters on the graph would represent periods of activity by a regiment. The peaks highlight some of the worst battles of the war.

The Spring Offensive

The greatest peak occurs on 21st March 1918. This say was the launch of the German Spring Offensive.

“The (german) artillery bombardment began at 4.40am on March 21st. The bombardment hit targets over and area of 150 square miles, the biggest barrage of the entire war. Over 1,100,000 shells were fired in five hours…”

The Germans made significant advances on this foggy morning. By the end of the day the British had lost nearly 20,000 (twenty thousand!) dead and 35,000 wounded,

Reuben Chilton was serving alongside Brierley Hill men with 2/6th Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment. The excellent Blackcountry-territorials.org website gives his description of that day:

The morning of March 21st was marked by the normal morning bombardment and an abnormally thick mist, making it impossible to see more than fifty yards ahead.

The first symptom of the coming evil was the fact that the normal bombardment did not diminish and cease in the normal way. On the contrary, it increased steadily, and eventually it became terrific, covering the whole area of our lines as far back as the transport.

Everywhere were heavy casualties, and notwithstanding the fact that through the mist the first small groups of the enemy were seen to be approaching, ” C ” Company could not go forward to support the others, because of the great gulf of impassable shelling between them. Of the fate of “A,” ” B ” and ” D ” Companies there is little to be said.

They were overwhelmed in the mist by the great advance, as a village lying at the foot of a volcano is completely submerged beneath the great stream of down-pouring lava.

” C ” Company was ordered to hold Railway Reserve Trench to the last, and there, under the command of Captain Jordan, it made its stand. The mist at the time (about a quarter-past eight o’clock) was rising slightly, and the sight it revealed was not a comforting one—masses of the enemy, south-east and soon directly south of Battalion Hqrs.

The German bombardment then lifted, in order to avoid its own troops. Battalion Hqrs. were rushed, and the CO. (Colonel Stuart Wortley) was killed. For as long as could be ” C ” Company held on, deprived of a platoon which had been thrown out to a flank, and reinforced instead by occasional remnants of the forward companies, men straggling back as best they could under the burden of their wounds and shell-suffering.

Against an overwhelming mass of advancing enemy, resistance could not be long protracted.

Our numbers became less and less, and, making a final stand in the communication trench, ” Tank Avenue,” the last remnant of the Company was joined from the rear by a returning stream of its own wounded bearing the news that the enemy were in force at the far end also of the trench.

When this remnant had been obliterated by death or wounds, but not until then, the resistance of the Battalion ceased, and the enemy passed through them, towards their transport lines now moved from Ervillers to Douchy.

Battle of Loos 1915

The second highest peak for Brierley Hill memorial deaths is a single day took place on 13th October 1915. This day marked the renewal of a British offensive seeking to regain ground lost earlier in the battle. Further details can be found on the website http://www.1914-1918.net/bat13.htm

1914-1919.net sates “…More than 61,000 British casualties were sustained in this batter …of these 7,766 men died”.

The website contains a chilling description of what happened at 2pm on 13th october.

6th (North Midland) Division sent 137th Brigade to attack on their right, to cross Big Willie and Dump Trench, to take Slag Alley and occupy Fosse Alley. To their left, 138th Brigade was to clear the Hohenzollern Redoubt and gain the Fosse 8 Corons. Thus the Dump itself was to be avoided and outflanked. On this front the gas barely moved, instead settling into shell holes and not reaching the enemy.

On leaving their positions, the advancing troops of 137th Brigade were immediately hit by heavy fire from machine guns concealed around the foot of the Dump and in the Corons. The attacking battalions were annihilated without achieving anything.

Of the two companies of the 1/5 South Staffords who were already holding a section of Big Willie, every single officer and man was hit as they tried to advance.

138th Brigade attacked at 2.05pm. They were to some extent sheltered from the machine-gunners at the Dump by the Hohenzollern Redoubt, and reached their first objectives in that area with fewer losses. On carrying on towards Fosse Trench, heavy fire from both the Dump and Mad Point cut across them causing very high casualties.

The attack came to a standstill within ten minutes. Isolated parties and men gradually returned to the shelter of the Redoubt. Trench fighting continued, but once again the shortage of bombs (which were of course outclassed by German ones) proved decisive.

The Division had lost 180 officers and 3,583 men within ten minutes, and achieved nothing.

It is highly likely then, that the four casualties listed on Brierley Hill war memorial died between 2pm and 2.05pm on that day. I’ve emphasised the paragraph which points out that every single soldier of 1/5 South Staffs in action that day was hit.

A tale of heroism

Finally in this post, there is the tale of another victim of the Battle of Loos.

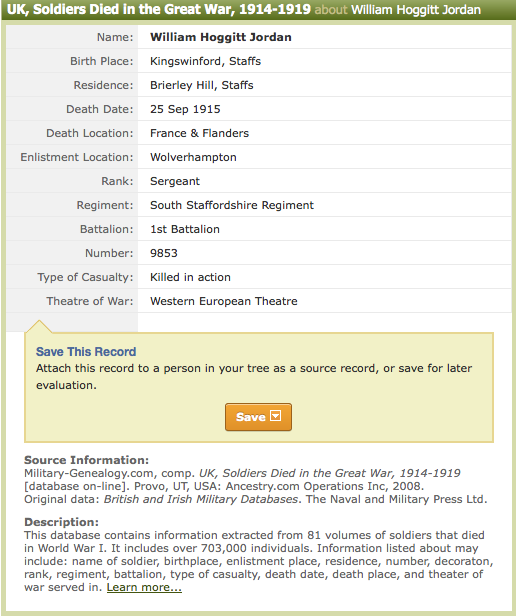

At the back of Brierley Hill library, out of sight and gathering dust, in one of the map drawers is a painting.

Underneath the painting is the inscription:

A BRIERLEY HILL HERO

Sergt. W. H. Jordan (South Staffs. Regt.) of Brockmoor, Brierley Hill, with great bravery stole out one night in May 1915. ‘somewhere in France’ and brought in a wounded comrade, who for two days had lain in an exposed position in front of our lines.

Sergt. Jordan was subsequently killed in the battle of Loos.

His widow received a letter, written in the name of the King, on recommendation of Field Marshal Sir John French, in praise of her husband’s bravery.

William Hoggitt Jordan’s name isn’t on the Brierley Hill war memorial. Perhaps it is on the memorial of his birth place in Kingswinford (NB since writing this article Joy Marshall has been in touch to let me know that he is commemorated on Brockmoor memorial). He died on 25th September 1915…the opening day of the Battle of Loos which was to take such a terrible toll.

A very enlightening article – and a great shame that the painting isn’t on prominent display in the library.

“He died on 25th September 2015…the opening day of the Battle of Loos which was to take such a terrible toll.”

The year of death is, of course, 1915.

I will correct the date. Thanks for pointing it out. It seems no matter how many times I proof read I always miss something!